When Ernest

Oberholtzer was 17, he suffered a severe bout of rheumatic fever that weakened

his heart. His doctors told him he wouldn’t survive the year. On June 6, 1977,

his damaged heart gave out and he died at the age of 93.

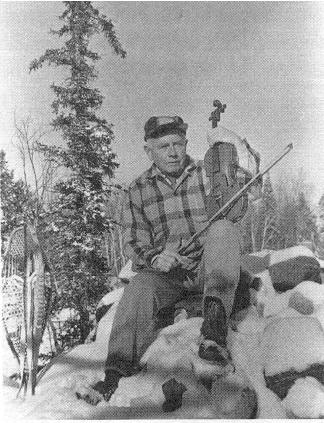

Ober was a man

of many passions. He studied the Ojibwe language at a time when our nation’s

policy was to suppress native culture and languages among Indian children. He

gathered Native American stories and legends. He photographed Indians and

wildlife, becoming famous for his photographs of moose. He played classical

violin, collected books, and entertained friends by the dozen on his small

Rainy Lake island. Though he never married, women were drawn to him, and one

in particular fell deeply in love with him.

Perhaps

his greatest

passion was his love of wilderness. He

devoted a major portion of his life to

protecting the U.S.-Canadian boundary waters

region, a place of “unsurpassed beauty,” an area he considered “one of the

rarest of all regions of

the continent, if not the world.”

He knew the Minnesota-Ontario

lakes region well. In 1907, when he was 23, he went on the first of his many

canoe trips. Five years later, he paddled with Ojibwe trapper and guide Billy

Magee across the Canadian Barrens to Hudson Bay and back, completing the

two-thousand-mile, four-month exploration in freezing temperatures and blowing

snow just before the onset of the sub-Arctic winter.

A little man possessed of the

courage to defeat an industrial giant, he fought to protect the Rainy Lake

watershed from those who would plunder and transform it. He spearheaded the

1930 defeat of a plan to build seven dams to convert the boundary waters lakes

into a four great storage basins for the production of industrial

hydroelectric power.

For fifty years

Ober made Mallard Island his home. Only eleven hundred feet in length

and without running water, the island contains seven buildings whose

construction was designed and supervised by Ober, two permanently grounded

boats, two pianos, and more than twelve thousand books, all carefully selected

and many mail-ordered by Ober. The buildings, some sided in cedar bark, rise

from their stone footings and blend harmoniously with the surrounding birch,

pine, and fir. One structure is a kitchen boat; another is reputed to have

been a floating whorehouse. On the east point, Front House looks to the

horizon across an open expanse of Rainy Lake’s some three hundred and thirty

square miles. On the west point, Japanese House, with its screened decks,

overlooks a bay cloistered by granite outcroppings and coniferous forest. To

the north and south, narrow channels separate Mallard from a cluster of

sheltering islands. Louise Erdrich describes the island as “the kind of

place that inspires a certain energy . . . a combination of erudition,

conservationism, nativism, and exuberant eccentricity.”

More than anything Ober wanted to

write. An avid reader and accomplished writer, he wrote dozens of articles,

thousands of letters to friends, and thousands more in support of his plan for

wilderness preservation, but he never achieved his lifelong ambition. He never

wrote a book about his canoe trips with Billy Magee, and he never wrote a book

about Native American legends – books that would justify his Harvard-educated

Northwoods existence, books whose royalties, he hoped, would solve his

lifelong financial problems. This failure haunted him as the great frustration

and disappointment of his life.

In his final years Ober

was robbed of his ability to speak by a series of minor strokes. But as reported

by Joe Paddock in

Keeper of the Wild: The Life of Ernest

Oberholtzer, he still had

good days. One day, the late Ted Hall, a former

correspondent and deputy New York bureau chief for Time-Life and publisher of

the Rainy Lake Chronicle, was pushing Ober in his wheelchair down a sidewalk

in International Falls. According to Hall, "The whole morning there

hadn’t been a word you could understand. He just communicated by signs. And as

we were crossing the street, an Indian woman called out to him and started a

conversation." Not until Ober’s friend had gone did Hall

realize that, in Ojibwe, Ober had been "completely, absolutely articulate."

After the conversation Ober once again "couldn’t get a word out."

![]()